By Susan Jennings

Article originally in the Winter 2021 Agraria Journal

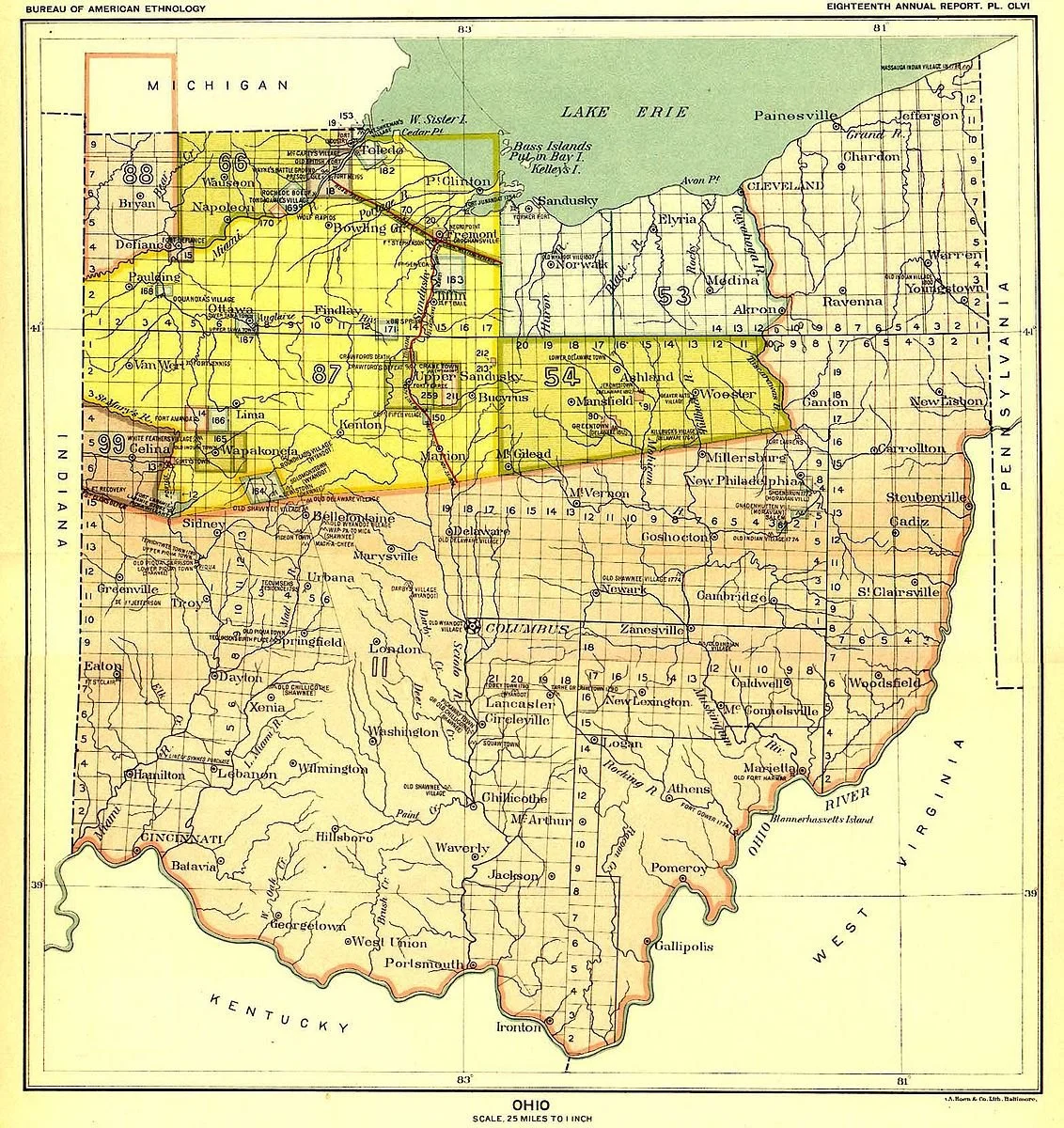

On Agraria, as in agricultural and “developed” land across the planet, farmers for decades pushed and prodded soil and water into straight lines. They felled trees, planted crops in rows, drained wetlands, and straightened streams to create more room for farming and building, turning a kaleidoscopic torrent of color, shape, and connection into a binary, monocultured and flattened grid. The channels gave water a straight shot from field to Jacoby Creek to river to sea, carrying along herbicides, fertilizers, and topsoil to a growing dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico.

Our signature work with The Nature Conservancy to remeander Jacoby Creek will regenerate natural shapes and forces and return the water to its fractal nature as it courses across land to hydrate it and nurture new life. With the planting of a native biodiverse streambank, the restoration will also prevent stream erosion, build new root systems, and enhance habitat. These multi-faceted benefits are characteristics of regenerative work that mimics natural systems.

Mechanistic approaches interrupt the synergistic dance between roots and soil, trees and sky with resultant damage to entire ecosystems. In contrast, regenerative practices can result in surprisingly rapid recovery, especially when they are structured like fractals or spirals, creating systems that are interconnected and allow for healing and evolution. This article explores the principles that inform such practices here at Agraria.

In 1975, IBM mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot discovered that the chaotic roughness that is shown in the static along electric lines—and also mirrored in coastlines and mountain ranges—can be described mathematically. While needing the power of computers to model, these self-similar and repeating patterns across scale and time are so ubiquitous as to be fundamental to how natural and other growth patterns express themselves. Mandelbrot coined the term fractals, and several years later wrote The Fractal Geometry of Nature to explain his evolving thought. We now recognize fractals not just in the way trees and rivers branch but also in the way that lightning and clouds spread. Animators use fractal geometry to create realistic landscapes for films. And anatomists know that blood runs through fractal vein systems, and that our lungs and other organs are also fractals.

Our brain has fractal characteristics, and our behaviors and perceptions display fractal patterns. The movements of investments and the market, population shifts, and community structures have fractal dynamics, and African indigenous knowledge systems, religion, architecture and textiles have fractals embedded in them.

If we are fractal creatures, it could explain why we love to spend time in the fractal light-filtered patterns of forests and are attracted to the fractal patterns of Jackson Pollack’s art.

Other mathematical patterns like the spirals of shells, pinecones and sunflowers; the Fibonacci sequence, which describes the growth of some spirals; the Phi ratio, which shows up in the Fibonacci sequence as well as in the length of our limbs and the shapes of our eyes; and Fourier transforms, which describe how we translate frequency into perception, suggest there is something profoundly rhythmic in the nature of growth and evolution—and in the nature of us. Bones, teeth, horns, shells, and trees grow in a spiraling pattern. You can also see spirals in the spin of galaxies and the swirling vortices of water as it flows across the landscape. In fact, these spirals may be how water is structured, producing a substance that is different than the bulk water that runs through our straight-line piping systems to our homes and through our irrigation systems.

Biomedical Engineering research scientist Gerald Pollack calls this the fourth phase of water—also the name of a book where he explores the phase of water that is neither liquid, solid nor vapor. This fourth kind of water cycles through our body and other natural systems and has a different chemical composition than bulk water, including an extra hydrogen molecule and an extra oxygen molecule. Structured water, as it is also known, can have a crystalline structure that resembles snowflakes. Pollack is not alone in noting that water—despite covering most of the planet and composing most of us—is not well understood nor adequately studied. Other researchers note that there are over 70 anomalous properties of water. What is clear is that the spiraling vortices of natural water systems and human anatomy cycle a water that is more complex and carries more information than the bulk water that flows through our straight-line systems.

If we zoom in carefully to just about everything we perceive, we might see that in fact all straight lines are imaginary and that there is much more to how life is structured for growth and evolution than our operating systems account for. Quantum physicist David Bohm believes that how we have shaped the world according to cartesian coordinate systems—the mathematics associated with mechanistic thinking—blinds us to the interconnected cyclical nature of natural systems. Our language, road systems, and engineering have literally boxed us into inaccurate if not damaging views of what we and the planet are shaped of.

Our paved-over planet and monocultured cropping systems not only interfere with natural cycles of transpiration and mycelial diversification and communication, but also impose on nature structures that are alien to growth and change. Much as a child’s drawing of a tree resembles a lollipop of a circle propped up by a stick, our simplistic understanding of the operating conditions of our planet ignores the realities of holistic systems that emerge out of the life principles that are encoded in quantum geometry. If life creates the conditions for life, as biomimicry genius Janine Benyus writes, then we might explore how our mechanistic structures are creating the conditions for death—including climate change, biodiversity collapse and declining human health.

Understanding the limits of cartesian grids and inhabiting a quantum planet and space time could wake us up from our planetary dark night where the progress that we thought we were making turns out to have been based on a simple geometric sense of success—added stuff, added jobs, added cities, added population. Quantum physics recognizes—as do indigenous cultures, Vedic scripture and Chinese philosophers—that time itself is cyclical and that death and rebirth are universal constants.

Paradoxically, moving out of the delusion of linear time as well as linear thinking can give us some sense of how to shape a different future.

We might look to the nature of fractals and spirals to recognize that ecosystems and human systems have many opportunities for growth, change, and reorganization. Complex natural systems are balanced between order and chaos—diversity produces robust and interconnected functioning. Redundancy supports stability and regrowth after disturbances. And emergent properties arise from complex systems that can’t be predicted but that produce a whole that is more than the sum of its parts.

Benyus coined the term biomimicry to describe human design that follows natural principles. This design movement has spiraled beyond her book and organization into multiple engineering, architectural, and design practices. Benyus’ ideas of using nature’s technologies, recipe books, and biological principles have inspired thousands of innovations, including fractal antennas and wind turbines that hold more information and interact with the surrounding environment in more complex ways than the standard models.

Permaculture, biodynamic farming, regenerative agriculture—and the indigenous practices on which these systems are based—echo fractal systems in their planting of multiple species and recognition of the patterns and flows of sunlight, seasons, wildlife, and people. Living walls and roofs, geodesic domes, and greywater filtering systems are patterns of building that seek to mimic and enhance the natural systems in which they are nested.

We are also coming to understand that there are emergent ways of working and sharing resources that can allow human communities to move like a murmuration of starlings into a different kind of thinking and doing. Rather than pooling talent and other resources into deep siloed wells, fractal ways of working—think creative intellectual commons and cooperative banks and enterprises—help to evolve not just individual partners but also the systems in which they partner.

Since our purchase of Agraria in 2017, we have been exploring regenerative practices on land and water—and in our modes of doing. We have transitioned 90 acres of the land out of conventional corn and soy to organic and permaculture plantings. Reforestation areas, perennial crops, and prairie plantings are echoes of the ecosystems that once covered our area. We know from soil studies and our own observation that mycelial networks are regrowing underground, and insect and bird populations are recouping above.

The re-meandering of Jacoby creek will likewise be studied for its impact on the regeneration of natural systems and the flora and fauna within and around the riparian zone.

Children and adults are engaged in nature-based play and exploration and learning about natural principles in conferences and workshops in ways that restore biophilic connections with the landscape and enhance understanding of how to regenerate it.

Our growth strategies are also fractal—exploring and cultivating the fertile land that intersects our main project areas. We are developing learning communities of staff, board, and friends to enhance our understandings. And we strive to develop partnerships that are mutually beneficial and move all of us toward more holistic understandings of our collective work. Examples of these partnerships are The Big Map Out project developed with The Yellow Springs Schools and research and extension partnerships with Central State University. Each of these partnerships draws on the expertise and expands the understandings and capabilities of all partners.

What we find emerging at Agraria and quickening in the midst of uncertainty and historic change is a commitment to inhabiting patterns of growth and evolution—a commitment to the shape of things to come.

Susan Jennings is executive director of Agraria Center for Regenerative Practice and co-editor of Agraria Journal.